By some estimates, such as from pawn shop observations or my storage room, there must be a billion guitars out there gathering dust, almost unused, bought in some burst of enthusiasm somewhere in life, abandoned before even “Smoke On the Water” sounded half decent, when the first sore fingers showed up. Same for keyboards. Or drum sets.

Along the same lines, there are likely a similar number of embryonic manuscripts sitting in computer folders across the world, when similarly people watch a great movie and think I can write that, and they go home and try, and abandon it after realizing the first three lines of dialogue don’t sound quite as much like Terminator as hoped.

And books. And songs.

The connection of those cultural abandonments to anything relevant passes through one of the hottest and seemingly overused phrases of the century: AI. And odd as it seems, these abandoned projects are wildly relevant to the topic. Here’s why.

It’s not crazy if your eyes are rolling reflexively at the mention of AI; the positive hype is a little bit berserk, while the doomsday crowd is in hyperbolic meltdown. The speculation is almost always bombastic. All lawyers will be replaced. Human workers will be obsolete. Robots will do everything humans can do with no laziness or attitude or union-forming. We will create the best virtual friends imaginable online, custom-made, interests and attitudes in perfect sync.

Wow, some life. Hyper productive yet super creepy. Impossible to imagine, yet hard not to see potential disaster. The whole potential gamut is so unsettling that I’m not even going to throw in a lawyer joke. And there’s always room for a lawyer joke.

It could be amazing, where major human challenges are resolved; maybe we’ll have perfected new food and housing and energy systems so that all will be fed and sheltered and warm. But such revolutions, even if positive, would have jarring and unsettling implementation challenges we can only guess at.

Or it could be a total disaster. Who knows. The truth will most likely be somewhere in the middle. But for now, for the next decade or two, we can narrow things down a bit. Luckily, there are smart people trying to make sense of it all. A tip of the hat to thoughtful people that passed on several highly intelligent and useful analyses of current trajectories, which are well worth digging into.

One is a podcast from Arc Energy Institute, a Jackie Forrest/Peter Tertzakian interview with Josh Schertzer, CEO of Beacon AI Centers. Schertzer discusses Beacon’s plans to develop half a dozen data centres in Alberta with a total potential power consumption of 4.5 GW. The conversation is an excellent, wide-ranging discussion about the nuances of data centres and their power consumption – how they work, the various characteristics, their requirements, etc.

The knowledge shared in this discussion is vital for a lot of people to absorb. We have two really strong forces that want to meet in the middle – a vast, ultra-wealthy, impatient tech sector that wants data centres NOW and is ready to pay whatever it takes, and a vast array of interests (governments, investors, power producers, energy industries of all sorts) that want to see data centres happen NOW as well. But it can’t happen all at once for many reasons that are not obvious, and this conversation does a great job of explaining the challenges. Anyone interested in data centres should listen. I won’t regurgitate them, would take far too long, but suffice it to say that there are many subtleties that need to resolved, ones that will take a lot of work no matter who wants them now.

The other is a monstrous (340 slide) presentation from a woman named Mary Meeker, who was a famous internet co analyst in the big dot com boom. She’s back with a wildly thorough look at AI from many angles, including the rapid rate of adoption. It may be huge but it is well worth reading; the charts really are mind-boggling.

As fundamental context for the growth of AI, Meeker’s report points out that 5.5 billion people are now internet connected. It took decades after the internet was introduced for much of the world to be connected and start using it. AI is not following the same path; anyone connected to the internet can leap right to AI and start reaping benefits. From the slide deck: it took Google 11 years to hit an annual search rate of 365 billion per year. It took ChatGPT just two years to reach the same number (will get back to this stat in a minute, it’s more important than it appears). Another rocket-ride stat: ChatGPT went from zero users in October 2022 to 800 million in April 2025. And ChatGPT is just one of many.

Long story short is that we really have no idea what AI will entail yet. That is one reason the forecasts run the gamut from complete disaster to complete nirvana. But we can see signs already of just how pervasive it will be, and – since we are here to talk about energy, right – just what an inevitable energy suck it I going to be.

Which finally brings us back to abandoned guitars and scripts. I picked those two because I can see them well, with two dusty guitars in a corner and plenty of writing that is only good for fire starter. These are presented as two simple examples of the power and power requirement of one simple aspect of humanity, the desire to make art of some kind.

Many, many people have an itch to make music, or to write, but do not get far. One reason is that either of these pastimes probably belongs in the “10,000 hour” bucket – you need to do something for that long to become truly proficient at it. Few make it past 10.0, or slightly more if they signed up for a bull pack of guitar lessons.

AI changes everything with respect to specific goals like this, in a simple but huge way. Let’s say you want to write a novel, and have tried but failed. So you get AI to help you, or even do it all for you so that you can tinker with it. AI will do that. There are various AI engines that will literally write a whole book for you when fed some prompts. Here is one such site, promising a novel “in minutes”. Hold that thought as well for a second – “in minutes”.

Here’s a site that allows all those frustrated pre-musicians to “write” their own songs. First you must dump in lyrics, but hey ChatGPT could write those for you first. Then you select a musical style, and a vocal style…boom there you go.

Of course, some of these packages require payment, and the more you pay the more you get. But here’s the critical part for energy folks.

How much computing power do you suppose it takes to generate an entire novel, or write a song? A clue is the “in minutes” part of the sales pitch. It’s not easy to gauge these things because of variability, and estimates have some error bars, but a typical power estimate seems to be as provided by this site: A typical Google query uses about 0.0003 kWh. A typical ChatGPT query uses about 0.0029 kWh – almost ten times as much.

That’s a pretty big leap, but then consider that a typical ChatGPT query – if there is such a thing yet – tends to be relatively simplistic, at least compared to a request to write a novel, which is going to be another order of magnitude in terms of power. Stats for these types of activities are not readily available yet (or maybe I just couldn’t find them), but think of the complexity.

A typical ChatGPT query is…well, might as well ask AI to find out! A Google query AI Overview says: A typical ChatGPT query is a simple question, prompt, or request that users input into the chatbot to elicit a response…often fall within the 100-word range and cover a wide variety of topics, from factual information to creative content generation, and can be used for entertainment, learning, or various other purposes.”

A novel is an entirely different beast when you think about how easy it can be to multiply complexity. Say you ask for a novel about 4 tourists in some random country that unearth a nefarious plot and solve a crime. It will take an AI engine “several minutes” to dredge up a novel. A Google search takes milliseconds, and even ChatGPT is seldom more than a few seconds. I don’t know what the power draw is, but a novel is going to be vastly more energy-intensive than “What is the best ice cream in the world.”

Then consider how the complexity can be multiplied with a few words. Make one of the book’s characters an expert in microbiology, and make one of them really funny. Now the workload is multiplied. Simply making one character an expert in a field might draw in an unbelievable amount of data to integrate, particularly if that is part of the story line.

And you can do this over and over and over just by making simple tweaks; if you paid for access you could generate a dozen novels per hour.

Same goes for music. Same goes for anything. And that’s just you noodling around. And the company providing the app that writes the novels does not really care about the power consumption, not if they can make a buck. And a lot of people expect to make a lot of bucks.

Imagine the impetus for industry to solve insanely complex problems. What if eating at least one banana per week wards off pancreatic cancer? How on earth would anyone know? Well, consider what the web knows about you, if credit card data can be integrated with medical records. What you buy at a grocery store shows up on receipts which show up on credit cards, which is valuable information which is why companies all want you to sign up for reward programs and to gather as much info as they can. Now imagine if Google or someone combined your search history with that data and cross referenced everything. Now imagine if that data is cross referenced with your phone’s data that includes how many steps you take every day and at what time of day. (Yeah yeah privacy concerns…that ship has sailed long ago people. There is a price to be paid for auto-clicking “I agree” to 50-page consent forms for everything we do online.)

In the span of just 2-3 years, what can be done with that data is revolutionary thanks to AI. It’s completely open-ended; the more data that is available, the more powerful these engines become, and the more they expand into new fields. Take Teslas, for example. Tesla is a pioneer in gathering data with all the cameras and sensors on the vehicle – video, temperature, you name it. Each Tesla is a data gathering machine, and all that info can be transformed into something useful. Maybe. Or maybe not. But the point is that every other auto maker will need to keep up to remain competitive.

And then take it one step further. Waymo and others are proving that self-driving works. Now combine that with say Starlink’s mobile wifi, and you have an office on wheels. Someone will build one soon, a little cube that can travel anywhere while you sit in the back sipping coffee and working on a computer and enjoying an endless panorama. That’s not all AI related, but it will be part of the picture and will turn it into yet another world we didn’t know could exist.

AI is guiding farmers by precision-zapping weeds instead of blanket spraying a field, and might be a really crazy boost to yields by studying weather, precipitation, historical yields, etc and figuring out some as yet unknown relationship. Data will be king. But also AI (and machine learning, AI’s dumber cousin) are helping sort recyclables better. How could that be a bad thing.

No one knows where this all ends up, which is the exciting part. Also the scary part. But one thing we do know: every step of the way, every advancement, every bigger/better AI machine – all will take power. Chips may get more efficient, but we’ll just use more of them.

Energy providers of all types – petroleum, nuclear, hydro, renewables -are the bedrock of all of this, and the future for the energy sector continues to get stronger.

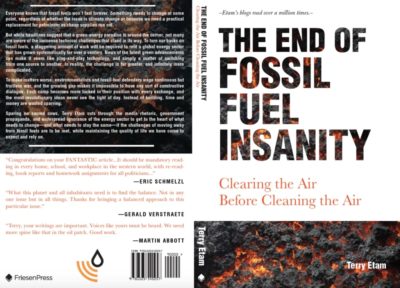

Explore the lighter side of energy, and think of it as you never have before in The End of Fossil Fuel Insanity – the energy story for those that don’t live in the energy world, but want to find out. And laugh. Available at Amazon.ca, Indigo.ca, or Amazon.com.

Email Terry here.